An Albertan in Europe: Rethinking what it means to travel

“London, UK? Wonderful! You’ll have so much fun. You can hop on a train and travel all over Europe!”

This was how almost everyone responded when I would tell them I was moving to the UK for graduate studies.

Indeed I did end up living in close proximity to King’s Cross Station, the origin point of many trains to other parts of Europe, and an easy Tube ride to the airport which could connect me easily to any continent in the world via direct flight. Living in Europe, and London specifically, certainly opens up the rest of the world in ways that are difficult to access in Western Canada.

King’s Cross St. Pancras, London, photo by Nabila Walji

I could have spent my years in graduate school hopping to a new country every other weekend, as many manage to do. But for some reason I didn’t want to. I wanted instead to explore all of London’s neighborhoods, and learn about the diasporic communities which made them famous. Plus, my mind at the time was still filled with the desire to visit Dakar, Mumbai, Dushanbe, Lagos, Istanbul, and Durban. (Not to mention, because of the pandemic, my captivation with what felt like a premature spring bloom was interrupted, and I returned to winter in Alberta.)

Walking London’s streets with my camera, or other European cities when I did travel, I felt lost. Everything was so beautiful, but I didn’t know why I was taking pictures of these beautiful sights (so many postcards, but no story) – how did they connect to me? In Europe, what was my story?

Some of those stories were hidden in plain sight. For instance, the azulejo tiles that cover many of Lisbon’s buildings, which are also found throughout Portugal, Spain and even across Europe. These tiles are a Portuguese national icon, but the name azulejo comes from the Arabic al-zillīj or الزليج, a term associated with tilework and used to designate a particular style of tilework employed by the Muslim rulers in the region to emulate Roman and Byzantine art and architecture in the 13th century.

Through time, a variety of other influences came into these tiles: Italian renaissance paintings, floral patterns inspired by textiles from South Asia, blue and white Chinese porcelain patterns. This craft, omnipresent throughout Portugal’s capital, represents the interactions between different cultures and times through socio-cultural, political and economic exchange. The later history of the azulejos tell another story: as European colonial powers expanded, the art and architecture of those they controlled were taken in bits and pieces, the inspiration for interior décor of drawing rooms. This was also the orientalization of the cultures they represented. Meanwhile, architectural styles from Europe were brought to their colonies; you can see azulejo tiles in South and North America too!

Musicians sitting in front of Azulejo tiles in Lisbon, Portugal, photo by Nabila Walji

In many parts of Europe, the grand sights that I was witnessing in fact spoke to one overarching word: colonialism. Beautiful as the sights may be, many stem from the fruits of colonialism of European countries in other countries. As a person of colour, I wondered even more where I fit in this place. Poignantly, some of POC friends explained the difficulty of growing up in England and identifying as English, when it was also the English who were responsible for much of the exploitation and violence in their homelands.

The products of colonial and imperial money became very visible upon my arrival to Oxford. The University of Oxford, founded between the 11th and 12th centuries, has a very long and interesting history. Many of its patrons in the 1700, 1800 and 1900s were significant to promoters and leaders of colonialism and imperialism. Most famously Cecil Rhodes, around which the ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ campaign has recurrently been in the news. At home, the campaign contributed to ongoing debates around some of our public statues and the names of public spaces as well.

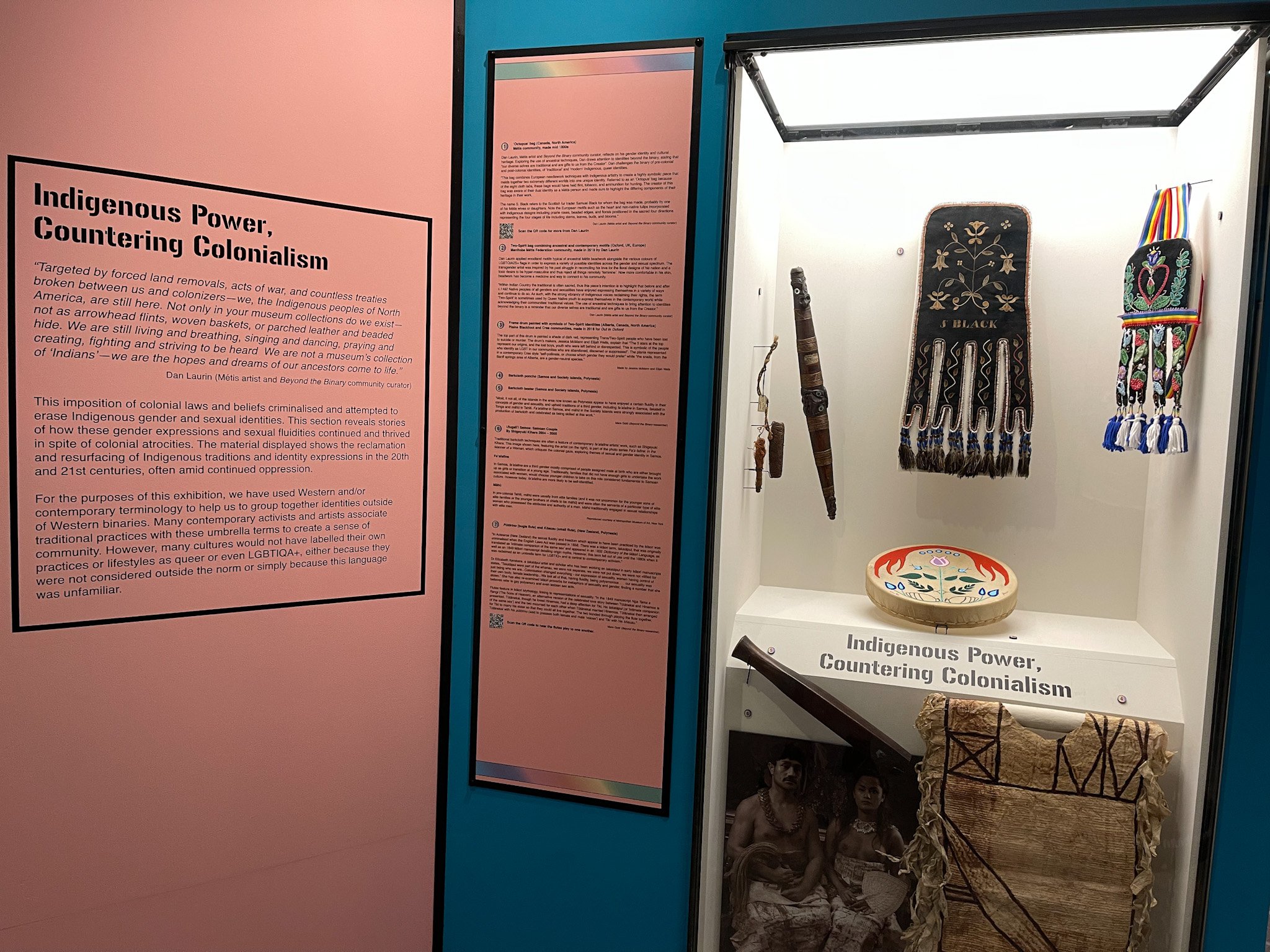

My current program of study in anthropology is tied to the Pitt Rivers Museum, the University’s museum of anthropology and world archeology which was founded in 1884. In my program, we learn extensively about the ties of the museum, anthropology and the University to colonialism and imperialism – and the harms done during these periods. We study the history of the objects, collections and their display, while constantly considering how this space can be decolonized, through repatriation of objects, improved labeling and by involving communities associated with the museum objects.

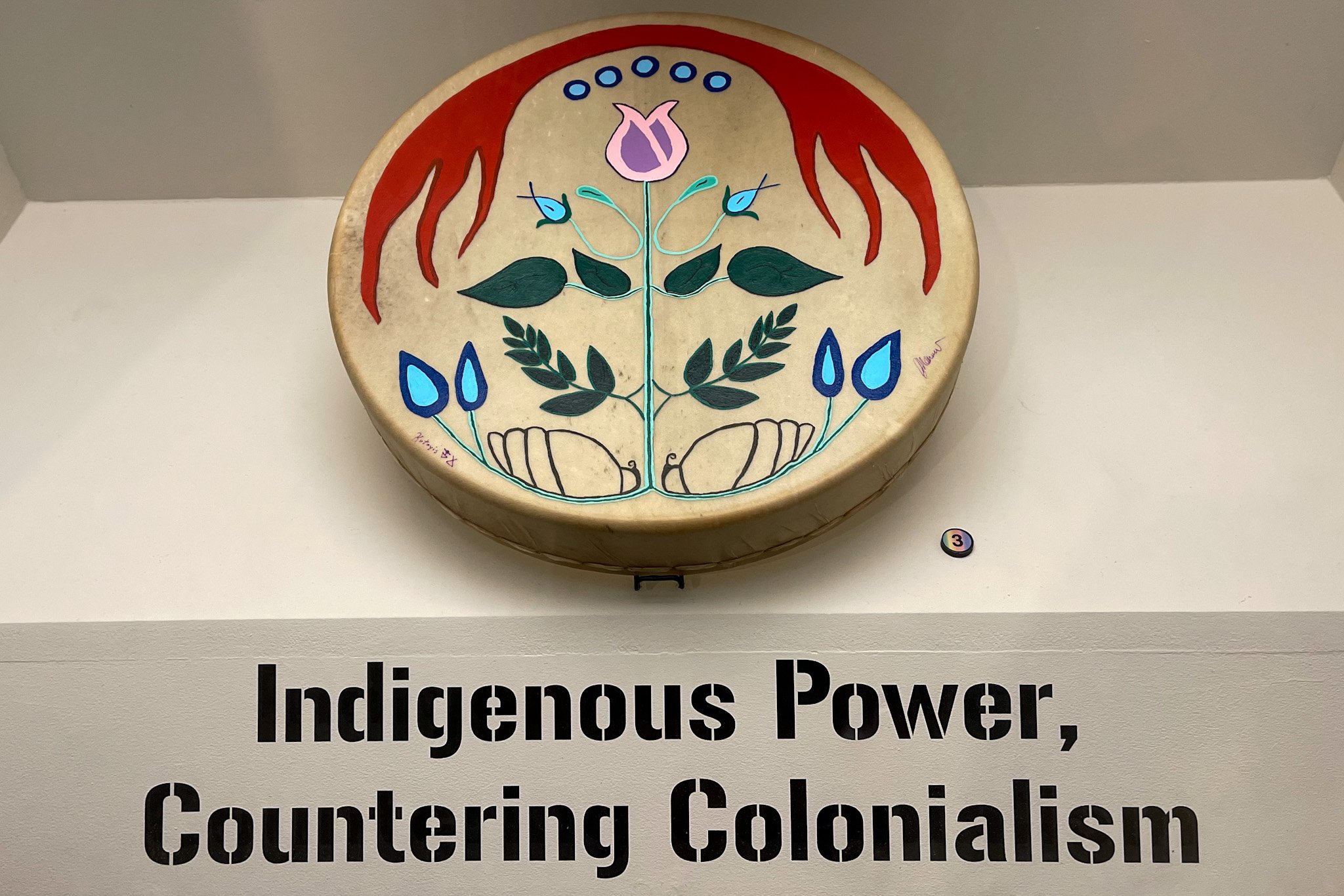

The museum does include some objects from Alberta. Among them is a tobacco pipe with beadwork collected around 1895 and donated to the Museum in 1952. The pipe is attributed to the Kainai Nation or Blackfoot Confederacy, and believed to have been carved by a prominent member of the community for ceremonial purposes. The Museum catalogue includes a researcher’s note that in 2004, two ceremonial leaders from the community examined the pipe and indicated that they believed the pipe was a fabrication made for tourists and was likely not a ceremonial pipe. Researching the history of objects on display at museums can reveal how they might well represent or misrepresent different cultures. Meanwhile the Pitt Rivers Museum purchased a painted frame drum made by Indigneous artists Elijah Wells and Jessica McMann, artists who have worked with Arts Commons, as part of their efforts to represent Indigenous voices in the museum. As explained on the Beyond the Binary exhibit panel, the painting on the drum represents Trans and Two-Spirit folks lost by the community to suicide or murder.

The exterior and interior of the Pitt Rivers Museum, the display case containing the beaded tobacco pipe (top right) and its associated display label, and photos of the painted frame drum made by Elijah Wells and Jessica McMann.

Organizations around the world are working to better educate locals and tourists about the complexity of cities. In Oxford, an organization called Uncomfortable Oxford sheds light on this history in the city, focusing on gender, race and colonialism in walking tours, guides, events and education projects that bring together locals, the University and tourists to engage more deeply with the city. The terms slow travel or conscious tourism have also become increasingly popular since the pandemic and highlight the importance of connecting with the places we visit, including their histories and challenges, while reducing climate impact. Wandering might take on new meanings once you study the travels of someone like Ibn Battuta. Instead of being a checkmark on a list, maybe travel should be about getting lost in order to understand one’s place in the universe?

Perhaps because Canada is a colonized land, we forget that the country continues to participate in harmful colonial practices. Among them is our glorification of Europe. We see it in our narratives about travel, where Europe is idealized as embodying culture, architecture and the highest of civilization. This is, in fact, a continuation of the logic through which colonialism was perpetuated – European civilization was deemed the highest to which all other cultures should aspire – and we still aspire to Europe in our visions of life and travel, to this day.

Travelling Europe is certainly a fantasy many of us hold: visiting grand European palaces, tasting its high culinary productions, witnessing history at their museums, and whimsically roaming the continent’s rivers and canals. You are well travelled when you’ve been to Europe, when you’ve seen the Eiffel tower, Westminster Abbey, the Sagrada Familia and so on – but not if you were born in Nigeria, have been to Colombia or know Alberta’s backroads like the back of your hand. Pop culture maintains this romanticization of Europe, but at least we no longer feel the need to walk around with Eiffel tower key chains on our bags and backpacks to suggest our “worldliness.”

Traveling can be necessary in many ways, but we can explore the world in new ways.

What’s wrong with exploring your own backyard? My photography in Canada focuses on stories of my family’s road trips through the continent - that was our summer holiday growing up (see #nabilasbackyard) - or considers BIPOC contributions and experiences in the country. Others are also writing about the value of telling stories of home.

By stopping all travel momentarily, the pandemic provided us with an opportunity to re-think what travel is, and what it should be. Maybe it's not about hitting all the icons a city or continent can offer, but slowing down and listening, smelling, tasting, feeling and seeing what the world around us says about everyday life in this place - both the obvious and those things hidden in plain sight.

As spring begins in the UK, my Albertan self cannot believe every new flower that blooms - isn’t it still winter? While many folks around me begin to travel the continent again during this break, I am blissful at home in Oxford, enraptured by the spring flowers bloom.

Who knows, in your backyard, you may find the entire world.

You can find more of Nabila’s work on Instagram @nabilawanders.